Hungary: Wasteland or Fertile Ground for Religious Tolerance?

'A device for attracting foreign skilled craftsmen to the new industries of Austria and settlers to the wastes of Hungary'. This is how Ernst Wangermann, writing in 1954, described the 1781 Patent of Toleration. Attracting settlers to the 'wastes of Hungary' exemplifies the lack of attention given to Hungary as an inferior part of the Habsburg Empire. Indeed, it is reflective of a broader interpretation of history that focuses on political developments in the centre of power, which during the time of the Habsburg Monarchy was Vienna. Rather than being insignificant, the story of the Edict of Toleration in Hungary is vital to understand the successes and failures of the history of religious toleration. The manuscripts of Mihály Virág located in the Klimó library in Pécs, are an important source for telling this story. They show that religious tolerance was viewed in a nuanced way, which recognised both the value of the ideals underlying religious problems as well as the practical problems created by the laws enacted. The story of religious toleration in Hungary provide an example of the limits of a centralised governance structure and the benefits of local contributions to policy development and implementation.

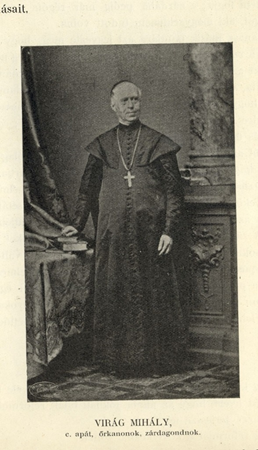

During our internship in Pécs, Hungary, we, Morten and Josh, blew away the dust from the manuscripts of Mihály Virág (1806-67) and investigated their contents. We presented the fruits of our labours at the Szépessy Ignac conference on 4th October 2018 in Pécs (the recording can be found here). The conference was jointly organised by the Diocese of Pécs, the University of Pécs and the Klimó Library. The Klimó library is recognised as the first library in Hungary open to the public and is named after its founder Bishop György Klimó, who came from a serf family and espoused the values of universal education and enlightenment. The conference focused on the history and contents of the library and brought together scholars from across Europe as well as academics local to Pécs. Among the other presentations given, it was highlighted that there is a significant edition of Origen's Works, which were published by Aldus Manutius. Virág was the librarian from 1835 to 1845 and contributed significantly towards the cataloging of its collections. In addition he was a professor of theology and canon of the cathedral. In his collection of manuscripts there are his lecture notes covering topics in Church history and Church law. We discovered that several of the manucripts are copied from published books of other authors, which give an indication of his source material and the dating of the manuscripts.

In several manuscripts, Virág deals with the topic of religious freedom and tolerance, giving special attention to its history in Hungary. He grounds the ideal of religious tolerance in theology, namely the inalienability of religious freedom based on the creation of human beings in the image of God. Hence he has a positive view of religious freedom but also displays concern about its limitations. These limitations were based in the practical complications of the religious tolerance laws on the lives of people in Hungary and in particular the Patent and Edict of Toleration, issued by Emperor Joseph II in 1781 and 1782, respectively. These laws produced curious results: For example, Protestants were granted permission to build churches but they were not allowed to have visible entrances facing the street and Jewish children had to attend Christian schools even though prior to the Edict they were free to be educated in Jewish communities. Virág also emphasises that it led to migration of Protestants between Croatia and Hungary. Virág bases his views on the practical problems created by the Edict. Consequently, he both appreciates and admonishes the implementation of religious tolerance in Hungary. It is important to recognise that he was not entirely negative towards religious toleration, as has often been assumed was the response of Catholics. Instead, he is careful to distinguish between the intellectual reasons behind toleration and the particular way it unfolded in history. In comparison to some recent studies on religion in 19th century Hungary, which conflate the intellectual and practical aspects of religious life in Hungary during this time, the distinction between intellectual and lay ideas provides an important supplement.

Virág’s manuscripts demonstrate that there was both a positive and negative reception of the laws on toleration in 19th century Hungary. Virág was familiar with the theological and philosophical movements of his time, as well as political and social developments. Our work supplements other studies on religious culture in Hungary during the Habsburg monarchy and showed a nuanced distinction between intellectual movements and the religious practices of the people. Thus the nuances of the historical development of religious freedom provide valuable context for understanding the state of religious freedoms in present-day Hungary. So we would like to conclude by suggesting that this may open new avenues of research in Hungarian church history. It is fitting to finish with a phrase that appears at the end of one of Virág’s manuscripts: 'Hát? már vége?!!' ('Well? Is it over?!!')

The presentation has been recorded and is available to listen here.